Функции excepthook() и exc_info() модуля sys в python

Содержание:

- Python Tutorial

- Raising Exceptions

- 8.5. Exception Chaining¶

- Настройка собственных классов исключений.

- «Голое» исключение

- Метод expect¶

- Повторите список в Python С Помощью Модуля Numpy

- Python Exception Handling: Error vs. Exception

- Argument of an Exception

- Конструкция try…finally

- User-Defined Exceptions

- The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

- Базовая структура обработки исключений

- Applying an except* Clause on One Exception at a Time

- Handling Multiple Exceptions with Except

- Raise Exception with Arguments

- Основные исключения

- Exceptions in Python

- Built-in Exceptions

- The try-finally Clause

- Catching specific exceptions

- Создание пользовательского класса исключений

- Перехват исключений в Python

Python Tutorial

Python HOMEPython IntroPython Get StartedPython SyntaxPython CommentsPython Variables

Python Variables

Variable Names

Assign Multiple Values

Output Variables

Global Variables

Variable Exercises

Python Data TypesPython NumbersPython CastingPython Strings

Python Strings

Slicing Strings

Modify Strings

Concatenate Strings

Format Strings

Escape Characters

String Methods

String Exercises

Python BooleansPython OperatorsPython Lists

Python Lists

Access List Items

Change List Items

Add List Items

Remove List Items

Loop Lists

List Comprehension

Sort Lists

Copy Lists

Join Lists

List Methods

List Exercises

Python Tuples

Python Tuples

Access Tuples

Update Tuples

Unpack Tuples

Loop Tuples

Join Tuples

Tuple Methods

Tuple Exercises

Python Sets

Python Sets

Access Set Items

Add Set Items

Remove Set Items

Loop Sets

Join Sets

Set Methods

Set Exercises

Python Dictionaries

Python Dictionaries

Access Items

Change Items

Add Items

Remove Items

Loop Dictionaries

Copy Dictionaries

Nested Dictionaries

Dictionary Methods

Dictionary Exercise

Python If…ElsePython While LoopsPython For LoopsPython FunctionsPython LambdaPython ArraysPython Classes/ObjectsPython InheritancePython IteratorsPython ScopePython ModulesPython DatesPython MathPython JSONPython RegExPython PIPPython Try…ExceptPython User InputPython String Formatting

Raising Exceptions

We can use raise keyword to throw an exception from our code. Some of the possible scenarios are:

- Function input parameters validation fails

- Catching an exception and then throwing a custom exception

class ValidationError(Exception):

pass

def divide(x, y):

try:

if type(x) is not int:

raise TypeError("Unsupported type")

if type(y) is not int:

raise TypeError("Unsupported type")

except TypeError as e:

print(e)

raise ValidationError("Invalid type of arguments")

if y is 0:

raise ValidationError("We can't divide by 0.")

try:

divide(10, 0)

except ValidationError as ve:

print(ve)

try:

divide(10, "5")

except ValidationError as ve:

print(ve)

Output:

We can't divide by 0. Unsupported type Invalid type of arguments

8.5. Exception Chaining¶

The statement allows an optional which enables

chaining exceptions. For example:

# exc must be exception instance or None. raise RuntimeError from exc

This can be useful when you are transforming exceptions. For example:

>>> def func():

... raise IOError

...

>>> try

... func()

... except IOError as exc

... raise RuntimeError('Failed to open database') from exc

...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in func

OSError

The above exception was the direct cause of the following exception:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 4, in <module>

RuntimeError: Failed to open database

Exception chaining happens automatically when an exception is raised inside an

or section. Exception chaining can be

disabled by using idiom:

>>> try

... open('database.sqlite')

... except OSError

... raise RuntimeError from None

...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 4, in <module>

RuntimeError

Настройка собственных классов исключений.

Для тонкой настройки своего класса исключения нужно иметь базовые знания объектно-ориентированного программирования.

Чтобы принимать дополнительные аргументы в соответствии с задачами конкретного исключения, необходимо дополнительно настроить пользовательский класс исключения.

Рассмотрим пример:

class SalaryNotInRangeError(Exception):

"""Исключение возникает из-за ошибок в зарплате.

Атрибуты:

salary: входная зарплата, вызвавшая ошибку

message: объяснение ошибки

"""

def __init__(self, salary, message="Зарплата не входит в диапазон (5000, 15000)"):

self.salary = salary

self.message = message

# переопределяется конструктор встроенного класса `Exception()`

super().__init__(self.message)

salary = int(input("Введите сумму зарплаты: "))

if not 5000 < salary < 15000

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)

В примере, для приема аргументов и переопределяется конструктор встроенного класса . Затем конструктор родительского класса вызывается вручную с аргументом при помощи функции . Пользовательский атрибут определен для использования позже.

Результаты запуска скрипта:

Введите сумму зарплаты: 2000

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 17, in <module>

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)

__main__.SalaryNotInRangeError: Зарплата не входит в диапазон (5000, 15000)

Унаследованный метод класса используется для отображения соответствующего сообщения при возникновении . Также можно настроить сам метод , переопределив его.

class SalaryNotInRangeError(Exception):

"""Исключение возникает из-за ошибок в зарплате.

Атрибуты:

salary: входная зарплата, вызвавшая ошибку

message: объяснение ошибки

"""

def __init__(self, salary, message="Зарплата не входит в диапазон (5000, 15000)"):

self.salary = salary

self.message = message

super().__init__(self.message)

# переопределяем метод '__str__'

def __str__(self):

return f'{self.salary} -> {self.message}'

salary = int(input("Введите сумму зарплаты: "))

if not 5000 < salary < 15000

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)

Вывод работы скрипта:

Введите сумму зарплаты: 2000

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 20, in <module>

raise SalaryNotInRangeError(salary)

__main__.SalaryNotInRangeError: 2000 -> Зарплата не входит в диапазон (5000, 15000)

«Голое» исключение

Есть еще один способ поймать ошибку:

Python

try:

1 / 0

except:

print(«You cannot divide by zero!»)

|

1 2 3 4 |

try 1 except print(«You cannot divide by zero!») |

Но мы его не рекомендуем. На жаргоне Пайтона, это известно как голое исключение, что означает, что будут найдены вообще все исключения. Причина, по которой так делать не рекомендуется, заключается в том, что вы не узнаете, что именно за исключение вы выловите. Когда у вас возникло что-то в духе ZeroDivisionError, вы хотите выявить фрагмент, в котором происходит деление на ноль. В коде, написанном выше, вы не можете указать, что именно вам нужно выявить. Давайте взглянем еще на несколько примеров:

Python

my_dict = {«a»:1, «b»:2, «c»:3}

try:

value = my_dict

except KeyError:

print(«That key does not exist!»)

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

my_dict={«a»1,»b»2,»c»3} try value=my_dict»d» exceptKeyError print(«That key does not exist!») |

Python

my_list =

try:

my_list

except IndexError:

print(«That index is not in the list!»)

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

my_list=1,2,3,4,5 try my_list6 exceptIndexError print(«That index is not in the list!») |

В первом примере, мы создали словарь из трех элементов. После этого, мы попытались открыть доступ ключу, которого в словаре нет. Так как ключ не в словаре, возникает KeyError, которую мы выявили. Второй пример показывает список, длина которого состоит из пяти объектов. Мы попытались взять седьмой объект из индекса.

Помните, что списки в Пайтоне начинаются с нуля, так что когда вы говорите 6, вы запрашиваете 7. В любом случае, в нашем списке только пять объектов, по этой причине возникает IndexError, которую мы выявили. Вы также можете выявить несколько ошибок за раз при помощи одного оператора. Для этого существует несколько различных способов. Давайте посмотрим:

Python

my_dict = {«a»:1, «b»:2, «c»:3}

try:

value = my_dict

except IndexError:

print(«This index does not exist!»)

except KeyError:

print(«This key is not in the dictionary!»)

except:

print(«Some other error occurred!»)

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

my_dict={«a»1,»b»2,»c»3} try value=my_dict»d» exceptIndexError print(«This index does not exist!») exceptKeyError print(«This key is not in the dictionary!») except print(«Some other error occurred!») |

Это самый стандартный способ выявить несколько исключений. Сначала мы попробовали открыть доступ к несуществующему ключу, которого нет в нашем словаре. При помощи try/except мы проверили код на наличие ошибки KeyError, которая находится во втором операторе except

Обратите внимание на то, что в конце кода у нас появилась «голое» исключение. Обычно, это не рекомендуется, но вы, возможно, будете сталкиваться с этим время от времени, так что лучше быть проинформированным об этом

Кстати, также обратите внимание на то, что вам не нужно использовать целый блок кода для обработки нескольких исключений. Обычно, целый блок используется для выявления одного единственного исключения. Изучим второй способ выявления нескольких исключений:

Python

try:

value = my_dict

except (IndexError, KeyError):

print(«An IndexError or KeyError occurred!»)

|

1 2 3 4 |

try value=my_dict»d» except(IndexError,KeyError) print(«An IndexError or KeyError occurred!») |

Обратите внимание на то, что в данном примере мы помещаем ошибки, которые мы хотим выявить, внутри круглых скобок. Проблема данного метода в том, что трудно сказать какая именно ошибка произошла, так что предыдущий пример, мы рекомендуем больше чем этот

Зачастую, когда происходит ошибка, вам нужно уведомить пользователя, при помощи сообщения.

В зависимости от сложности данной ошибки, вам может понадобиться выйти из программы. Иногда вам может понадобиться выполнить очистку, перед выходом из программы. Например, если вы открыли соединение с базой данных, вам нужно будет закрыть его, перед выходом из программы, или вы можете закончить с открытым соединением. Другой пример – закрытие дескриптора файла, к которому вы обращаетесь. Теперь нам нужно научиться убирать за собой. Это очень просто, если использовать оператор finally.

Метод expect¶

Метод expect позволяет указывать список с регулярными выражениями. Он

работает похоже на pexpect, но в модуле telnetlib всегда надо передавать

список регулярных выражений.

При этом, можно передавать байтовые строки или компилированные

регулярные выражения:

In 22]: telnet.write(b'sh clock\n')

In 23]: telnet.expect('])

Out23]:

(,

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(46, 47), match=b'>'>,

b'sh clock\r\n*19:35:10.984 UTC Fri Nov 3 2017\r\nR1>')

Метод expect возвращает кортеж их трех элементов:

- индекс выражения, которое совпало

- объект Match

- байтовая строка, которая содержит все

считанное до регулярного выражения и включая его

Соответственно, при необходимости, с этими элементами можно дальше

работать:

Повторите список в Python С Помощью Модуля Numpy

Третий способ перебора списка в Python – это использование модуля Numpy. Для достижения нашей цели с помощью этого метода нам нужны два метода numpy, которые упоминаются ниже:

- numpy.nditer()

- numpy.arange()

Iterator object nditer предоставляет множество гибких способов итерации по всему списку с помощью модуля numpy. Функция href=”http://numpy.org/doc/stable/reference/generated/numpy.nditer.html”>nditer() – это вспомогательная функция, которая может использоваться от очень простых до очень продвинутых итераций. Это упрощает некоторые фундаментальные проблемы, с которыми мы сталкиваемся в итерации. href=”http://numpy.org/doc/stable/reference/generated/numpy.nditer.html”>nditer() – это вспомогательная функция, которая может использоваться от очень простых до очень продвинутых итераций. Это упрощает некоторые фундаментальные проблемы, с которыми мы сталкиваемся в итерации.

Нам также нужна другая функция для перебора списка в Python с помощью numpy, которая является numpy.arrange().numpy.arange возвращает равномерно распределенные значения в пределах заданного интервала. Значения генерируются в пределах полуоткрытого интервала [start, stop) (другими словами, интервала, включающего start, но исключающего stop).

Синтаксис:

Синтаксис numpy.nditer()

Синтаксис numpy.arrange()

- start: Параметр start используется для предоставления начального значения массива.

- stop: Этот параметр используется для предоставления конечного значения массива.

- шаг: Он обеспечивает разницу между каждым целым числом массива и генерируемой последовательностью.

Объяснение

В приведенном выше примере 1 программа np.arange(10) создает последовательность целых чисел от 0 до 9 и сохраняет ее в переменной x. После этого мы должны запустить цикл for, и, используя этот цикл for и np.nditer(x), мы будем перебирать каждый элемент списка один за другим.

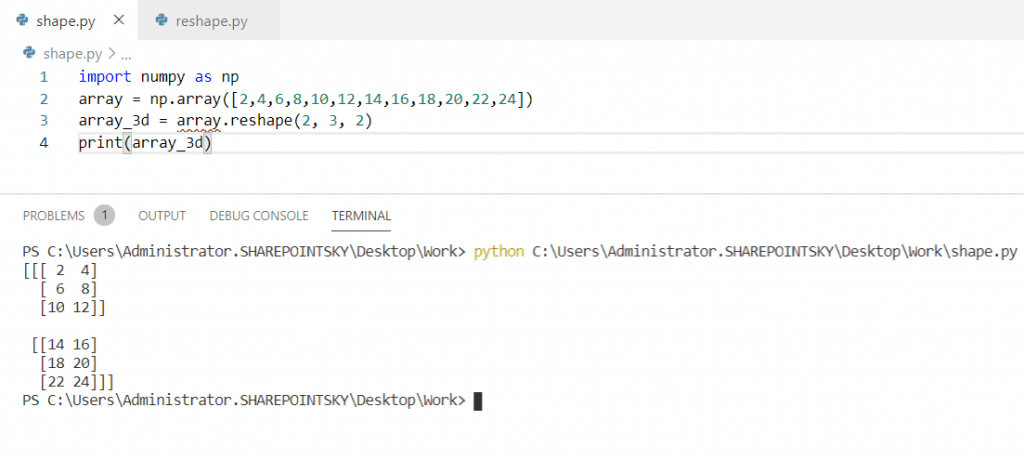

Пример 2:

В этом примере мы будем итерировать 2d-массив с помощью модуля numpy. Для достижения нашей цели нам здесь нужны три функции.

- numpy.arange()

- numpy.reshape()

- numpy.nditer()

import numpy as np .arange(16) .reshape(4, 4) for x in np.nditer(a): print(x)

Объяснение:

Большая часть этого примера похожа на наш первый пример, за исключением того, что мы добавили дополнительную функцию numpy.reshape(). Функция numpy.reshape() обычно используется для придания формы нашему массиву или списку. В основном на непрофессиональном языке он преобразует размеры массива-как в этом примере мы использовали функцию reshape(), чтобы сделать массив numpy 2D-массивом.

Python Exception Handling: Error vs. Exception

What is Error?

The error is something that goes wrong in the program, e.g., like a syntactical error.

It occurs at compile time. Let’s see an example.

if a<5

File "<interactive input>", line 1

if a < 5

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

What is Exception?

The errors also occur at runtime, and we know them as exceptions. An exception is an event which occurs during the execution of a program and disrupts the normal flow of the program’s instructions.

In general, when a Python script encounters an error situation that it can’t cope with, it raises an exception.

When a Python script raises an exception, it creates an exception object.

Usually, the script handles the exception immediately. If it doesn’t do so, then the program will terminate and print a traceback to the error along with its whereabouts.

>>> 1 / 0 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<string>", line 301, in run code File "<interactive input>", line 1, in <module> ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Argument of an Exception

An exception can have an argument, which is a value that gives additional information about the problem. The contents of the argument vary by exception. You capture an exception’s argument by supplying a variable in the except clause as follows −

try: You do your operations here ...................... except ExceptionType as Argument: You can print value of Argument here...

If you write the code to handle a single exception, you can have a variable follow the name of the exception in the except statement. If you are trapping multiple exceptions, you can have a variable follow the tuple of the exception.

This variable receives the value of the exception mostly containing the cause of the exception. The variable can receive a single value or multiple values in the form of a tuple. This tuple usually contains the error string, the error number, and an error location.

Example

Following is an example for a single exception −

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Define a function here.

def temp_convert(var):

try:

return int(var)

except ValueError as Argument:

print ("The argument does not contain numbers\n", Argument)

# Call above function here.

temp_convert("xyz")

This produces the following result −

The argument does not contain numbers invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'xyz'

Конструкция try…finally

Инструкция может также иметь и необязательный блок . Этот блок кода будет выполнен в любом случае и обычно используется для освобождения внешних ресурсов.

Например, мы можем быть подключены через сеть к удаленному дата-центру, или работать с файлом или с GUI (Graphical User Interface — графический интерфейс пользователя).

Во всех таких случаях мы должны закрыть эти ресурсы вне зависимости от того, успешно завершилась наша программа или нет. Все эти действия (закрытие файла или GUI, отключение от сети) можно выполнять в блоке , чтобы гарантировать их исполнение.

Вот пример операций с файлом, который иллюстрирует это:

try:

f = open("test.txt",encoding = 'utf-8')

# perform file operations

finally:

f.close()

Такая конструкция гарантирует нам, что файл будет закрыт в любом случае, какое бы исключение в работе кода не возникло.

User-Defined Exceptions

Python also allows you to create your own exceptions by deriving classes from the standard built-in exceptions.

Here is an example related to RuntimeError. Here, a class is created that is subclassed from RuntimeError. This is useful when you need to display more specific information when an exception is caught.

In the try block, the user-defined exception is raised and caught in the except block. The variable e is used to create an instance of the class Networkerror.

class Networkerror(RuntimeError):

def __init__(self, arg):

self.args = arg

So once you have defined the above class, you can raise the exception as follows −

try:

raise Networkerror("Bad hostname")

except Networkerror,e:

print e.args

Previous Page

Print Page

Next Page

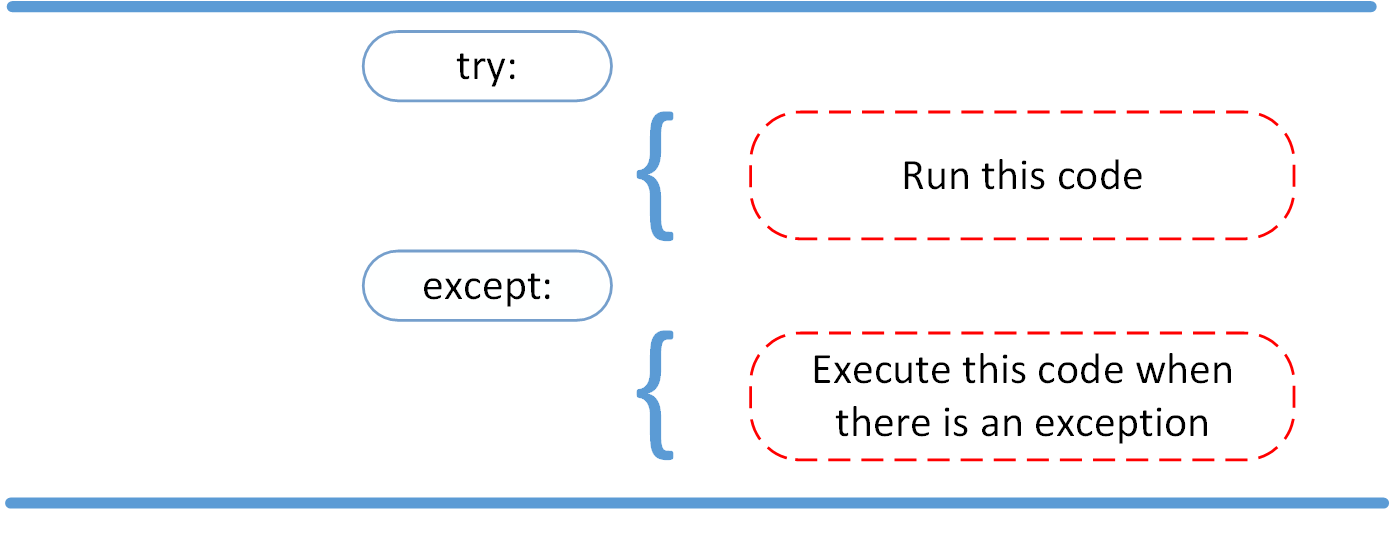

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

The and block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

The following function can help you understand the and block:

The can only run on a Linux system. The in this function will throw an exception if you call it on an operating system other then Linux.

You can give the function a using the following code:

The way you handled the error here is by handing out a . If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, you would get the following output:

You got nothing. The good thing here is that the program did not crash. But it would be nice to see if some type of exception occurred whenever you ran your code. To this end, you can change the into something that would generate an informative message, like so:

Execute this code on a Windows machine:

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the and output that message to screen:

Running this function on a Windows machine outputs the following:

The first message is the , informing you that the function can only be executed on a Linux machine. The second message tells you which function was not executed.

In the previous example, you called a function that you wrote yourself. When you executed the function, you caught the exception and printed it to screen.

Here’s another example where you open a file and use a built-in exception:

If file.log does not exist, this block of code will output the following:

This is an informative message, and our program will still continue to run. In the Python docs, you can see that there are a lot of built-in exceptions that you can use here. One exception described on that page is the following:

To catch this type of exception and print it to screen, you could use the following code:

In this case, if file.log does not exist, the output will be the following:

You can have more than one function call in your clause and anticipate catching various exceptions. A thing to note here is that the code in the clause will stop as soon as an exception is encountered.

Warning: Catching hides all errors…even those which are completely unexpected. This is why you should avoid bare clauses in your Python programs. Instead, you’ll want to refer to specific exception classes you want to catch and handle. You can learn more about why this is a good idea in this tutorial.

Look at the following code. Here, you first call the function and then try to open a file:

If the file does not exist, running this code on a Windows machine will output the following:

Inside the clause, you ran into an exception immediately and did not get to the part where you attempt to open file.log. Now look at what happens when you run the code on a Linux machine:

Here are the key takeaways:

- A clause is executed up until the point where the first exception is encountered.

- Inside the clause, or the exception handler, you determine how the program responds to the exception.

- You can anticipate multiple exceptions and differentiate how the program should respond to them.

- Avoid using bare clauses.

Базовая структура обработки исключений

В предыдущем разделе мы продемонстрировали, как возникает исключение и как с этим справиться. В этом разделе мы обсудим базовую структуру кодирования для обработки исключений. Таким образом, базовая структура кода для обработки исключений в Python приведена ниже.

name = 'Imtiaz Abedin'

try:

# Write the suspicious block of code

print(name)

except AssertionError: # Catch a single exception

# This block will be executed if exception A is caught

print('AssertionError')

except (EnvironmentError, SyntaxError, NameError) as E: # catch multiple exception

# This block will be executed if any of the exception B, C or D is caught

print(E)

except :

print('Exception')

# This block will be executed if any other exception other than A, B, C or D is caught

else:

# If no exception is caught, this block will be executed

pass

finally:

# This block will be executed and it is a must!

pass

# this line is not related to the try-except block

print('This will be printed.')

Здесь вы можете видеть, что мы используем ключевое слово except в другом стиле. Первое ключевое слово except используется для перехвата только одного исключения, а именно исключения AssertionError.

Однако, как видите, второе ключевое слово except используется для перехвата нескольких исключений.

Если вы используете ключевое слово except без упоминания какого-либо конкретного исключения, оно перехватит любое исключение, созданное программой.

Блок else будет выполнен, если не будет найдено исключение. Наконец, независимо от того, будет ли обнаружено какое-либо исключение, будет выполнен блок finally.

Итак, если вы запустите приведенный выше код, мы получим результат:

Если вы измените name на nameee в приведенном выше коде, вы получите следующий результат:

Applying an except* Clause on One Exception at a Time

We explained above that it is unsafe to execute an except clause in

existing code more than once, because the code may not be idempotent.

We considered doing this in the new except* clauses,

where the backwards compatibility considerations do not exist.

The idea is to always execute an except* clause on a single exception,

possibly executing the same clause multiple times when it matches multiple

exceptions. We decided instead to execute each except* clause at most

once, giving it an exception group that contains all matching exceptions. The

reason for this decision was the observation that when a program needs to know

the particular context of an exception it is handling, the exception is

handled before it is grouped and raised together with other exceptions.

For example, KeyError is an exception that typically relates to a certain

operation. Any recovery code would be local to the place where the error

occurred, and would use the traditional except:

try:

dct

except KeyError:

# handle the exception

It is unlikely that asyncio users would want to do something like this:

try:

async with asyncio.TaskGroup() as g:

g.create_task(task1); g.create_task(task2)

except *KeyError:

# handling KeyError here is meaningless, there's

# no context to do anything with it but to log it.

Handling Multiple Exceptions with Except

We can define multiple exceptions with the same except clause. It means that if the Python interpreter finds a matching exception, then it’ll execute the code written under the except clause.

In short, when we define except clause in this way, we expect the same piece of code to throw different exceptions. Also, we want to take the same action in each case.

Please refer to the below example.

Example

try: You do your operations here; ...................... except(Exception1]]): If there is any exception from the given exception list, then execute this block. ...................... else: If there is no exception then execute this block

Raise Exception with Arguments

What is Raise?

We can forcefully raise an exception using the raise keyword.

We can also optionally pass values to the exception and specify why it has occurred.

Raise Syntax

Here is the syntax for calling the “raise” method.

raise ]]

Where,

- Under the “Exception” – specify its name.

- The “args” is optional and represents the value of the exception argument.

- The final argument, “traceback,” is also optional and if present, is the traceback object used for the exception.

Let’s take an example to clarify this.

Raise Example

>>> raise MemoryError

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

MemoryError

>>> raise MemoryError("This is an argument")

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

MemoryError: This is an argument

>>> try:

a = int(input("Enter a positive integer value: "))

if a <= 0:

raise ValueError("This is not a positive number!!")

except ValueError as ve:

print(ve)

Following Output is displayed if we enter a negative number:

Enter a positive integer: –5

This is not a positive number!!

Основные исключения

Вы уже сталкивались со множеством исключений. Ниже изложен список основных встроенных исключений (определение в документации к Пайтону):

- Exception – то, на чем фактически строятся все остальные ошибки;

- AttributeError – возникает, когда ссылка атрибута или присвоение не могут быть выполнены;

- IOError – возникает в том случае, когда операция I/O (такая как оператор вывода, встроенная функция open() или метод объекта-файла) не может быть выполнена, по связанной с I/O причине: «файл не найден», или «диск заполнен», иными словами.

- ImportError – возникает, когда оператор import не может найти определение модуля, или когда оператор не может найти имя файла, который должен быть импортирован;

- IndexError – возникает, когда индекс последовательности находится вне допустимого диапазона;

- KeyError – возникает, когда ключ сопоставления (dictionary key) не найден в наборе существующих ключей;

- KeyboardInterrupt – возникает, когда пользователь нажимает клавишу прерывания(обычно Delete или Ctrl+C);

- NameError – возникает, когда локальное или глобальное имя не найдено;

- OSError – возникает, когда функция получает связанную с системой ошибку;

- SyntaxError — возникает, когда синтаксическая ошибка встречается синтаксическим анализатором;

- TypeError – возникает, когда операция или функция применяется к объекту несоответствующего типа. Связанное значение представляет собой строку, в которой приводятся подробные сведения о несоответствии типов;

- ValueError – возникает, когда встроенная операция или функция получают аргумент, тип которого правильный, но неправильно значение, и ситуация не может описано более точно, как при возникновении IndexError;

- ZeroDivisionError – возникает, когда второй аргумент операции division или modulo равен нулю;

Существует много других исключений, но вы вряд ли будете сталкиваться с ними так же часто. В целом, если вы заинтересованы, вы можете узнать больше о них в документации Пайтон.

Exceptions in Python

Python has many built-in exceptions that are raised when your program encounters an error (something in the program goes wrong).

When these exceptions occur, the Python interpreter stops the current process and passes it to the calling process until it is handled. If not handled, the program will crash.

For example, let us consider a program where we have a function that calls function , which in turn calls function . If an exception occurs in function but is not handled in , the exception passes to and then to .

If never handled, an error message is displayed and our program comes to a sudden unexpected halt.

Built-in Exceptions

The table below shows built-in exceptions that are usually raised in Python:

| Exception | Description |

|---|---|

| ArithmeticError | Raised when an error occurs in numeric calculations |

| AssertionError | Raised when an assert statement fails |

| AttributeError | Raised when attribute reference or assignment fails |

| Exception | Base class for all exceptions |

| EOFError |

Raised when the input() method hits an «end of file» condition (EOF) |

| FloatingPointError | Raised when a floating point calculation fails |

| GeneratorExit | Raised when a generator is closed (with the close() method) |

| ImportError | Raised when an imported module does not exist |

| IndentationError | Raised when indendation is not correct |

| IndexError | Raised when an index of a sequence does not exist |

| KeyError | Raised when a key does not exist in a dictionary |

| KeyboardInterrupt |

Raised when the user presses Ctrl+c, Ctrl+z or Delete |

| LookupError | Raised when errors raised cant be found |

| MemoryError | Raised when a program runs out of memory |

| NameError | Raised when a variable does not exist |

| NotImplementedError |

Raised when an abstract method requires an inherited class to override the method |

| OSError | Raised when a system related operation causes an error |

| OverflowError | Raised when the result of a numeric calculation is too large |

| ReferenceError | Raised when a weak reference object does not exist |

| RuntimeError | Raised when an error occurs that do not belong to any specific expections |

| StopIteration | Raised when the next() method of an iterator has no further values |

| SyntaxError | Raised when a syntax error occurs |

| TabError | Raised when indentation consists of tabs or spaces |

| SystemError | Raised when a system error occurs |

| SystemExit | Raised when the sys.exit() function is called |

| TypeError | Raised when two different types are combined |

| UnboundLocalError | Raised when a local variable is referenced before assignment |

| UnicodeError | Raised when a unicode problem occurs |

| UnicodeEncodeError | Raised when a unicode encoding problem occurs |

| UnicodeDecodeError | Raised when a unicode decoding problem occurs |

| UnicodeTranslateError | Raised when a unicode translation problem occurs |

| ValueError | Raised when there is a wrong value in a specified data type |

| ZeroDivisionError | Raised when the second operator in a division is zero |

❮ Previous

Next ❯

The try-finally Clause

You can use a finally: block along with a try: block. The finally block is a place to put any code that must execute, whether the try-block

raised an exception or not. The syntax of the try-finally statement is this −

try: You do your operations here; ...................... Due to any exception, this may be skipped. finally: This would always be executed. ......................

You cannot use else clause as well along with a finally clause.

Example

#!/usr/bin/python

try:

fh = open("testfile", "w")

fh.write("This is my test file for exception handling!!")

finally:

print "Error: can\'t find file or read data"

If you do not have permission to open the file in writing mode, then this will produce the following result −

Error: can't find file or read data

Same example can be written more cleanly as follows −

#!/usr/bin/python

try:

fh = open("testfile", "w")

try:

fh.write("This is my test file for exception handling!!")

finally:

print "Going to close the file"

fh.close()

except IOError:

print "Error: can\'t find file or read data"

When an exception is thrown in the try block, the execution immediately passes to the finally block. After all the statements in the finally block are executed, the exception is raised again and is handled in the except statements if present in the next higher layer of the try-except statement.

Catching specific exceptions

When you enter the net sales of the prior period as zero, you’ll get the following message:

In this case, both net sales of the prior and current periods are numbers, the program still issues an error message. Another exception must occur.

The statement allows you to handle a particular exception. To catch a selected exception, you place the type of exception after the keyword:

For example:

When you run a program and enter a string for the net sales, you’ll get the same error message.

However, if you enter zero for the net sales of the prior period:

… you’ll get the following error message:

This time you got the exception. This division by zero exception caused by the following statement:

And the reason is that the value of the is zero.

Создание пользовательского класса исключений

Мы можем создать пользовательский класс исключения, расширяя класс исключения. Лучшая практика состоит в том, чтобы создать базовое исключение, а затем выводить другие классы исключения. Вот несколько примеров создания пользовательских классов исключения.

class EmployeeModuleError(Exception):

"""Base Exception Class for our Employee module"""

pass

class EmployeeNotFoundError(EmployeeModuleError):

"""Error raised when employee is not found in the database"""

def __init__(self, emp_id, msg):

self.employee_id = emp_id

self.error_message = msg

class EmployeeUpdateError(EmployeeModuleError):

"""Error raised when employee update fails"""

def __init__(self, emp_id, sql_error_code, sql_error_msg):

self.employee_id = emp_id

self.error_message = sql_error_msg

self.error_code = sql_error_code

Конвенция об именовании заключается в суффиксе имени класса исключения с «Ошибками».

Перехват исключений в Python

В Python исключения обрабатываются при помощи инструкции .

Критическая операция, которая может вызвать исключение, помещается внутрь блока . А код, при помощи которого это исключение будет обработано, — внутрь блока .

Таким образом, мы можем выбрать набор операций, который мы хотим совершить при перехвате исключения. Вот простой пример.

# Для получения типа исключения импортируем модуль sys

import sys

randomList =

for entry in randomList:

try:

print("The entry is", entry)

r = 1/int(entry)

break

except:

print("Oops!", sys.exc_info(), "occurred.")

print("Next entry.")

print()

print("The reciprocal of", entry, "is", r)

Результат:

В данном примере мы, при помощи цикла , производим итерацию списка . Как мы ранее заметили, часть кода, в которой может произойти ошибка, помещена внутри блока .

Если исключений не возникает, блок пропускается, а программа продолжает выполнятся обычным образом (в данном примере так происходит с последним элементом списка). Но если исключение появляется, оно сразу обрабатывается в блоке (в данном примере так происходит с первым и вторым элементом списка).

В нашем примере мы вывели на экран имя исключения при помощи функции , которую импортировали из модуля . Можно заметить, что элемент вызывает , а вызывает .

Так как все исключения в Python наследуются из базового класса , мы можем переписать наш код следующим образом:

# Для получения типа исключения импортируем модуль sys

import sys

randomList =

for entry in randomList:

try:

print("The entry is", entry)

r = 1/int(entry)

break

except Exception as e:

print("Oops!", e.__class__, "occurred.")

print("Next entry.")

print()

print("The reciprocal of", entry, "is", r)

Результат выполнения этого кода будет точно таким же.